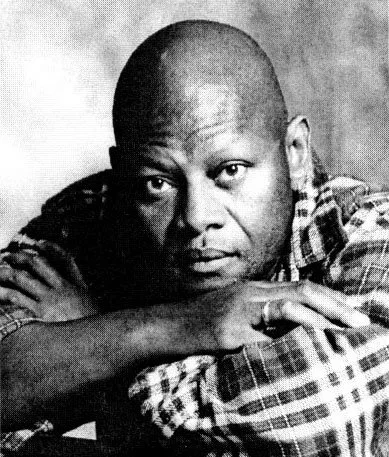

ABOUT

LEON E. PETTIWAY

The Ven. Lobzang Dorje

MONK · SCHOLAR · WRITER

Photo credit: Michelle Jarvis/Candice Baggertt

I am committed to investigating the social, economic, and political issues influencing the life chances of all sentient beings.

This is actualized and reflected in my writings, nurtured by the spiritual teachings on compassion and wisdom, and revealed through invited lectures. I am particularly interested in discussions centering on social inequality and the administration of justice.

SPIRITUALITY

Leon E. Pettiway is one of a few African American fully-ordained Buddhist monks in the Gelug tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, receiving novice vows in 2002 and full ordination in 2005.

In his childhood, members of his family were Southern Baptists, but he converted to Catholicism when he was a junior in college. For most of his adult life, he was a rather devout Catholic until his early 50s when he stumbled onto Buddhism. That encounter was one of the more profound and transformative experiences of his life.

While blackness has been a ruthless teacher, the wisdom of the Buddha’s Dharma has enabled him to realize that the Dharma was more than just words on a page. So, when he considers all the issues and obstacles he encountered as a person of African descent, he believes he was extremely fortunate to come into being with black skin. The Dharma is life, experienced as projections of the ultimate nature of reality suffused with love.

In 2016, he established Dagom Geden Kunkyob Ling Buddhist Monastery in Indianapolis, Indiana to preserve the precious teachings and to offer them to others.

ACADEMIC

He received his PhD in urban and social geography from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in 1979 and has held teaching positions at North Carolina Central University, Prairie View A & M University, Temple University, the University of Delaware, and Indiana University, Bloomington. Currently, he is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Criminal Justice at Indiana University, Bloomington.

Early in his academic career, Professor Pettiway conducted research that integrated geographical and criminological theories to explain patterns of crime in urban areas. In that regard, he has published articles on the impact of race and ghettoization on patterns of crime participation, the role of environmental and individual factors in arson, the relationship between an individual’s drug use and criminal participation with respect to the formation of crime partnerships, and the criminal decision-making process of addicts and nonusers in light of various environmental cues. Currently, his intellectual work centers on the construction of knowledge and how Eastern and Western philosophical traditions might be integrated into criminological theory and the administration of justice.

Photo credits: Paul Riley, Indiana University Photographic Services; Judy Kelley

When he received a very large grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), he conducted field research from a storefront in Philadelphia where he interviewed drug users and offenders about their drug use and crime participation. That experience altered his academic career, and from that research, he completed Honey, Honey, Miss Thang: Being Black, Gay, and on the Streets, a Finalist for the 9th Annual Lambda Literary Award (Temple University Press), which examined the lives of drug-addicted, transgender women who commit a variety of crimes. Workin’ It: Women Living Through Drugs and Crime (Temple University Press) chronicled the drug use and crime participation of a group of inner-city women, which was also from the research in Philadelphia. The experience of conducting field research touched him deeply, and it provided him the opportunity to reflect on issues of race, crime, and justice in ways that were not tied to failed socialization, dysfunction, and pathology. Only for the Brave at Heart: Essays Rethinking Race, Crime, and Justice, slated to be published in the fall of 2023, attempts to create an intellectual movement that re-imagines notions of race, crime, and the administration of justice.

As Professor Emeritus, his intellectual work centers on the construction of knowledge and the ways Eastern and Western philosophical traditions might be integrated into criminological theory and the administration of justice, focusing on the intersections of race, crime, and justice. In his retirement, he focuses on his spiritual practice and his academic and creative writing.

PERSONAL

Growing from a boy to manhood in the South seems so long ago, but back then, a black child dared not drink from the same water fountain as a white person, and while I was born to folks who had little formal education, my father was a successful businessman and provided for us in extraordinary ways. My parents sheltered me from much of the ugliness of racism during my youth, but I’ve often considered how segregation provided me with some precious gifts: learning not to be distracted or dissuaded by what others thought my status should be, that there are worlds outside of what I experienced, and there were no limits to what could be dreamed.

I also grew up in a home that was turbulent; there were times when I was so worried for my mother’s safety, living with a man like my father. He was my first example of the complex of being—a man who was a supreme provider but was also an abuser. He was one of my great teachers because he helped to realize who and what I didn’t want to become. Without the great lessons learned as a black boy in the racist South and in a home with an abusive father, who would I be?

So, I acknowledge the great lessons and blessings given to me by my parents, who passed so, so long ago, and I hope they are proud of the human being I have become. I express my gratitude to my mother and father; they taught me to hope, planted the seeds for compassion, and made it possible for me to dream greater dreams than they had or could have ever imagined.